|

The 2021 notebook is available here

Judy Malloy: A writer's notebook is not a final paper but rather reflects the development of a work or series of works. In the informal, recursive, yet productive practice of creating notebooks online, ideas and sources are developed and slowly emerge. This 2018-2019 notebook is about the creation of Arriving Simultaneously on Multiple Far-Flung Systems and beginning in the Fall of 2018, it is also about reconstructing The Yellow Bowl, and transmediating the BASIC version of its name was Penelope.

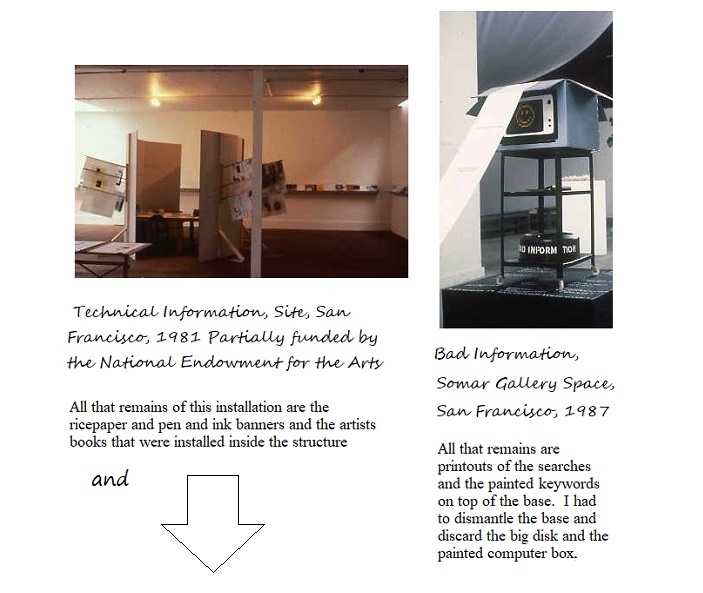

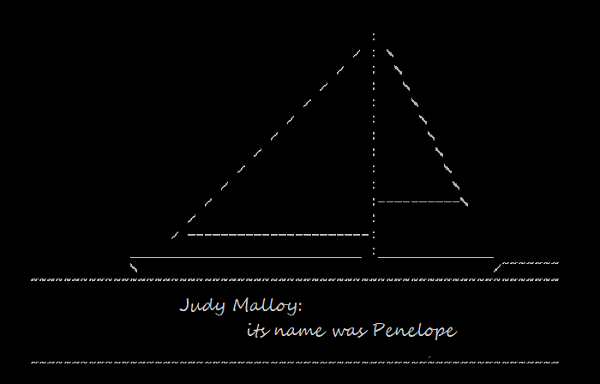

February 7, 2020 T he magnificent. snowstorm -- during which traditionally I have closed a notebook and begun another one -- has not yet occurred. Thus, it is in early February, on one of a series of seemingly endless gray rainy days in New Jersey, that this "February, 2018 - February 2020 Writer's Notebook" closes. The reconstruction of the BASIC version of its name was Penelope is now available in an https version at https://people.well.com/user/jmalloy/penelope/ In this JavaScript version, the sailboat that in the BASIC version (but not in the Eastgate version) moved across the screen, accompanied by sound, has been restored -- as if it is a messenger from pre-web screen-based electronic literature, or contingently from the time of Homer, when writing technologies may have begun to seep into storytelling. Considering how often and in how many languages The Odyssey has been retold, it is relevant to emphasize that there are many ways of carrying a work forward through the centuries. Thus, I'd like to applaud those who are exploring different ways to do this for computer-mediated artworks. A few thoughts: 1. There are artists for whom the work's destruction or short life are a part of the work. William Gibson's Agrippa, is a good example. However, eventual obsolescence is not the goal of most artists who create computer-mediated artworks. 2. Preservation projects and experimental methods of preservation should be funded. The work of artists to translate their own works for new platforms should also be funded. Those of us who teach should be urging students to score their works and to keep notebooks about the process. And I am happy to continue to make my work accessible in contemporary fluctuating software/hardware environments. 3. The voices of artists were not listened to when Frames were no longer supported, when Flash was no longer supported, when Apple changed its OS so that pre-existing artworks were no longer supported, when autoplay was no longer supported, when artworks were censored on social media, when browsers began to discriminate against small providers. We need public advocacy for taking into account the needs of artists when such changes are made. We need an artwork-centered browser. 4. It should be remembered that, including painting, there are many vibrant, central to art-making genres where preservation is an issue. In some cases, this is known at the time of creation; in others it is not known. For instance, I can no longer play audio tape cassettes from early performances, but I did not anticipate this. On the other hand, I'm not the only artist who has had to throw away the materials from a completed installation because there was no place to store them. Nevertheless, I am happy that a detailed notebook of all the materials I used in the Technical Information installation is in my archives at the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Duke University. And an artists book with searches from the first Bad Information Base is also in my archives.

5. It is relevant to consider how many centuries it took for music notation (for better or worse) to be standardized. December 31, 2019

"They lifted the mast and stept it in its hollow box,

Homer, The Odyssey. Book II.

its name was Penelope

This year, December was a time for reading and criting the extraordinary final projects created by my School of the Art Institute Art and Technology Studies, Social Media Narratives Class. This December, I have also been working on archiving Blueskying a Social Media Platform for the Arts, the online panel the class hosted from November 7-12, 2019. The panelists' statements, the discussion, and my introduction to the whole are now in working draft form, and I look forward to releasing documentation of the entire panel in January. Early January of every other year is also the time when my notebooks -- that usually span two years -- conclude. A new notebook is traditionally started at the end of January, often blown in with a substantial snowstorm. Meanwhile Happy New Year! November 3, 2019

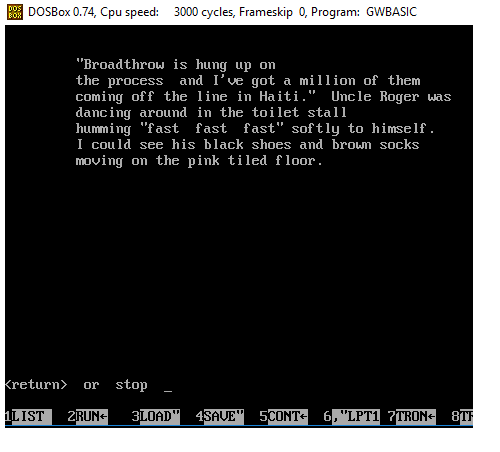

"Of these events, Muse,

With the pleasure of exploring and responding to student midterms in my SAIC ATS Social Media Narratives class and with careful final editing on The Yellow Bowl, October has swiftly passed. The third Social Media Narratives class panel on "Issues in Social Media for the Arts" begins at the end of this week. And now the time has come to complete the 2019 year of writing and coding with a web-situated version of the 1990 its name was Penelope, which was originally coded in BASIC and distributed on floppy disk via the Art Com Media Distribution catalog. Re-tooled by Mark Bernstein in a Storyspace look and feel environment, the Eastgate its name was Penelope remains the definitive published version. I am hoping that sometime in the future the Eastgate version will be available for contemporary platforms. Meanwhile, the JavaSrcipt in an HTML5/CSS version, scheduled to be finished by the end of 2019, will provide scholars with easy access to a version that will very closely follow the original BASIC edition. The BASIC version of its name was Penelope has been available for DOSBox since I re-created it on Critical Code Studies from Jan 18 to Feb 14, 2016. The JavaScript version is conceived as being the same as this 2016 recreation, but it will not require loading DOSBox, and will run directly from the Web. "In an art medium such as performance, where life often becomes the total content of the work. life can also become the form, with little or no distinction between where art stops and life begins... Any discussion of performance must consider the lives and experiences of the artists producing the work." -- Carl Loeffler, Performance Anthology, Source Book for a Decade of California Performance Art, Contemporary Arts Press, 1980. Quoted in Lexia #63 of its name was Penelope. Dene Grigar has summarized the versions of this work in her essay "Memory, the Muse, and Judy Malloy's its name was Penelope". The original work on the BASIC version of its name was Penelope, a tale of the San Francisco Bay area art world in the 1980's, was begun in 1988 after I finished "Terminals", the third file of Uncle Roger. An exhibition version, created in 1989, was shown in the "Revealing Conversations" exhibition at the Richmond Art Center, curated by Zlata Baum, and also including the work of Lynn Hershman, Sonya Rapoport, and Steve Wilson, among others. For distribution, subsequently I retooled the exhibition version into the 1990 Narrabase Press edition. This pre-Eastgate Penelope was reviewed in 1992 by Nancy Princenthal in The Print Collector's Newsletter, where she called it "a thoroughly beguiling piece of fiction..." I'm happy to report that on November 1, 2019. I began work on the web version of its name was Penelope. The animated sailboat that sails across the screen in the BASIC version is working. The audio that accompanies the motion of the boat was produced in BASIC directly from code. I would prefer to do this directly from JavaScript but am not sure this is possible. I may have to record the sound from the original BASIC version. The code that drives "The Grace Files" in The Yellow Bowl, was derived (with some changes) from the authoring system I created for its name was Penelope. Thus, because I have already converted this code to JavaScript, other than formatting the screen display and the usual difficulties with precise formatting of JavaScript strings, the recreation of the body of its name was Penelope will not be too difficult. I have begun with "dawn, the childhood file.

"The star that foretells dawn September 27, 2019

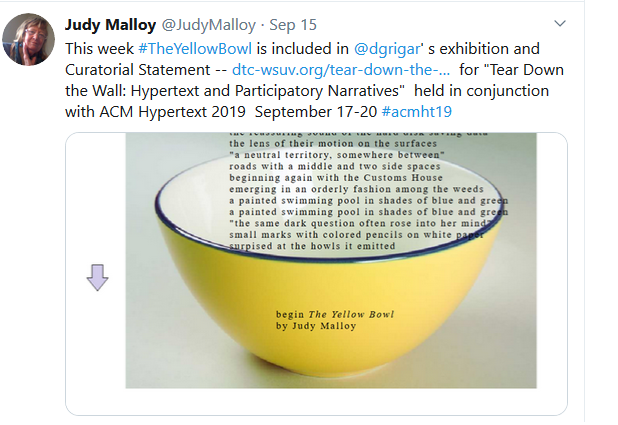

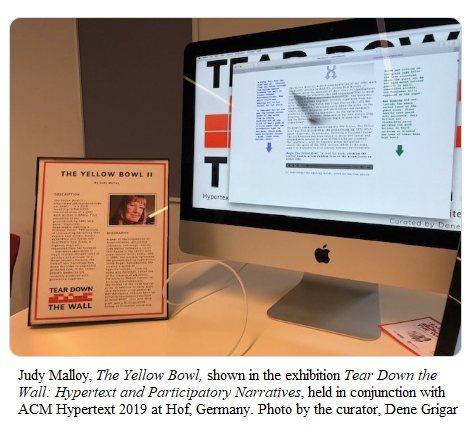

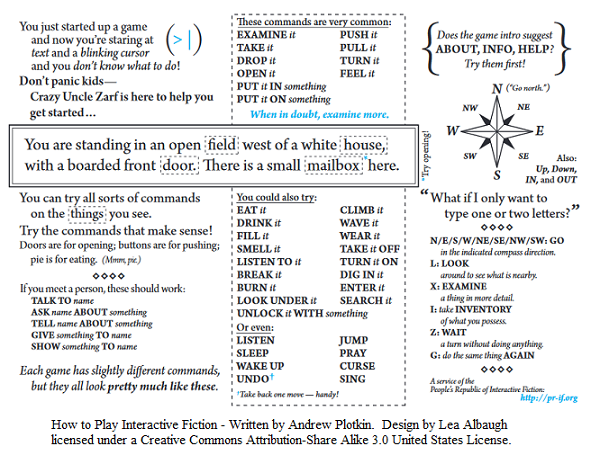

The Yellow Bowl has returned from exhibition at ACMHT19 in Hof, Germany. A mild post-partum depression often accompanies the ending of such events, even if they are only experienced via Twitter. Contingently, I read Interactive Fiction writer and critic Emily Short's review: "The Yellow Bowl (Judy Malloy) and Hypertexts of Juxtaposition" I very much like Short's conclusion: "Meanwhile, I felt The Yellow Bowl got at something about the simultaneous tracks of a mental life, and about how our memories and ideas, fictions and physical realities all ping off one another; about how the past and the present, the read and the imagined, can coexist in our minds in an exceptionally vivid way, and indeed be in dialogue with each other and influence our actions from moment to moment every day. It does so more extensively, I think, than any of the other juxtapositional IF or hypertext I’ve mentioned above — and makes me wonder what more could be done in this space." It should be noted that although both Interactive Fiction (IF) and electronic literature challenge readers with active reading experiences, hypertext literature confronts the reader with interaction, screen display, and content that is very different from the experience of negotiating IF. In Of Two Minds, Michael Joyce observes that: "Print stays itself; electronic text replaces itself. If with the book we are always printing -- always opening another text unreasonably composed of the same gestures -- with electronic text we are always painting, each screen unreasonably washing away what was and replacing it with itself." (p 186) Because the text -- that parser-based interaction in Inform7-authored works produces -- is often stable, Joyce's vision may appear surprising to a writer steeped in IF -- just as students new to IF are sometimes stymied by the commands that are required to negotiate Interactive Fiction.

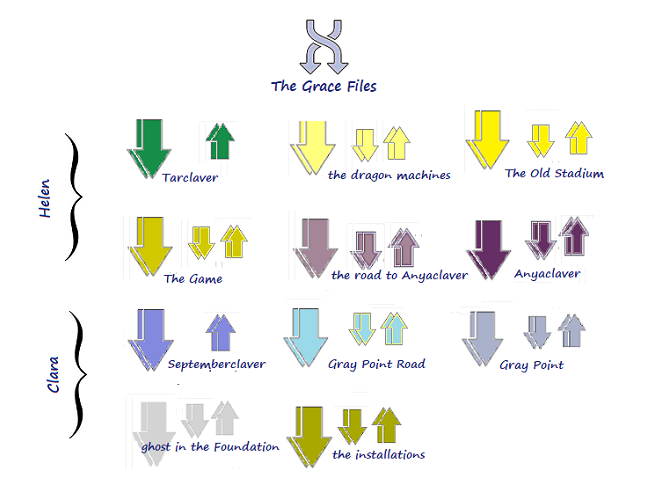

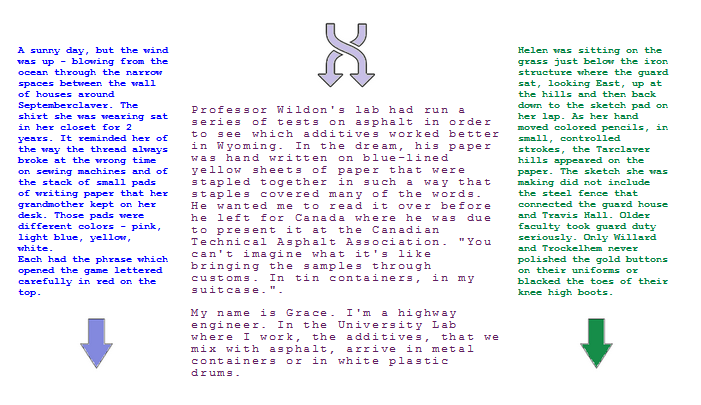

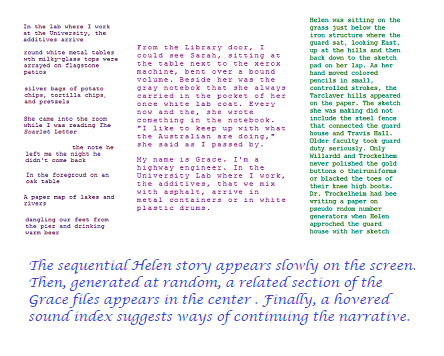

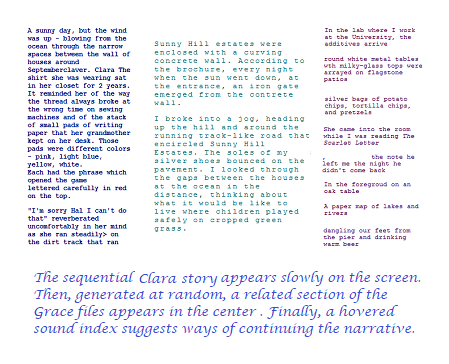

Hypertext works also exhibit occasionally frustrating interaction with the system. This may primarily in be in the form of navigating a complex system, but the reader-challenging role of animated text is also basic to many works of electronic literature. It is expected practice in generative poetry (Nick Montfort's Taroko Gorge, for instance). It is general practice in kinetic electronic poetry (Oni Buchanan's The Mandrake Vehicles, for instance). It invigorates electronic manuscripts (Maria Mencia's Gateway to the World and Gottfried Haider's Hidden in Plain Sight, for instance), and it is often inherent in Cave works (Jeneen Naji's The Rubayaat for instance). In The Yellow Bowl, animated text simulates the oral story-telling aspect of the Helen and Clara stories -- where the listener cannot hurry the reader. Within the narrastructure, animated text delivery was also used to distinguish the text in the Helen/Clara stories from the text of "The Grace Files". Although it could be said that hypertext literature is more sophisticated in terms of content and variety of authoring systems, personally I'm not inclined to preference electronic literature over Interactive Fiction, anymore than I'm inclined to preference electronic literature over print -- or print over electronic literature and its sister, Interactive Fiction. August 31- September 1, 2019 The Yellow Bowl II houses a text stream of generative hypertext in the midst of two sequential text streams -- one on each side of the generative hypertext-produced "The Grace Files". At the time, 1991, when this work was begun, I was interested in augmenting hypertextual practice using a tri-part structure; using generative hypertext as one element in this structure; and using implicit linking between all elements of the structure. Now, in this writer's notebook, for the next few months, I'm documenting how this structure evolved.

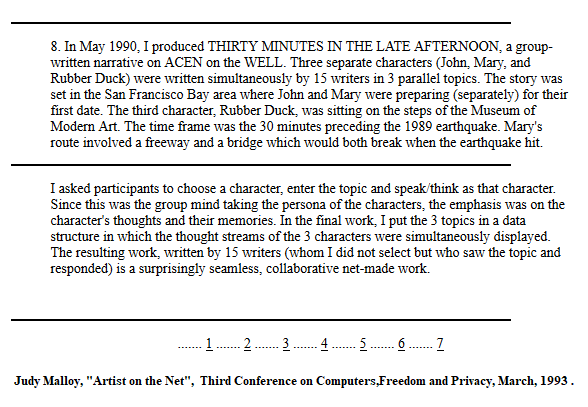

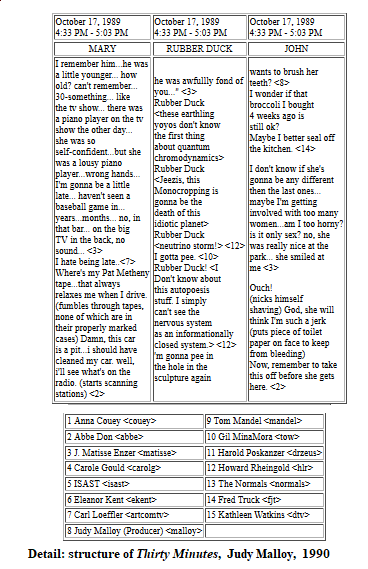

It is sometimes difficult to document social media-platform based collaborative work. Thus, when invited to publish Thirty Minutes in Art Com Magazine, [1] I struggled to create a structure that would convey the narrative. Given that there were three characters, a 3-col structure was a logical way to do this. The idea was suggested by a dream I had in which information about waste streams was displayed in three separate but parallel streams of text that spewed side by side in readable type size from overhead printers on an auditorium stage. (At that time, I worked for a chemical engineering company that R&Ded environmental technologies.) The October 1990 Art Com Magazine version of Thirty Minutes was static. I liked the way it conveyed the story, but it lacked the energy inherent in the real-time group creation of Thirty Minutes -- where it was the unpredictable responses of the participants that drove interest in the narrative. A few years later, I would address this issue in Wasting Time. When working in experimental genres, there are often surprising discoveries of precursor works of which we did not know and/or of which we had only a dim memory. Three column structures for instance were not unknown in print literature, beginning (if not earlier) with ancient manuscripts for Exodus 15 1-19. In mainframe-mediated electronic literature, the earliest precursor is probably Dick Higgins' edgy "Hank and Mary, a Love Story, a Chorale" (circa 1969.) Written by Higgins and programmed in FORTRAN IV by Higgins and James Tenney, this mainframe computer-printer-realized work is remarkable for the complex polyphonic ballad it produces with multi-col permutations of only four words: "HANK SHOT MARY DEAD". [2] In publishing Thirty Minutes in the Late Afternoon, I sought also to credit the authors without interfering with the flow of the work. In his First Monday 1997 paper "The Internet Oracle: Virtual Authors and Network Community", David R. Sewell observes that: "...in the collaborative fiction "Thirty Minutes in the Late Afternoon" created and published on the Whole Earth 'Lectronic Link (WELL) in 1990, editor Judy Malloy rearranged posted contributions to create a seamless narrative in parallel columns, but used parenthetical numbers linked to author names to identify the individual contributions. When claims are made, then, that the electronic medium inherently tends to assimilate the solitary author to a network or collaborative group, they need to be tested critically against the actual practice of writers on the nets.

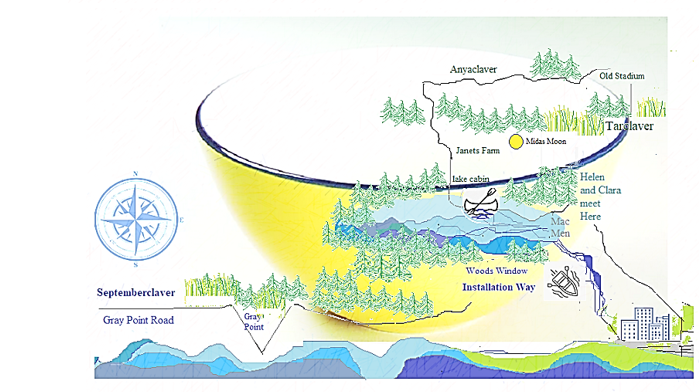

1. Judy Malloy, "Thirty Minutes in the Late Afternoon", ART COM Magazine 10:8, October, 1990. August 10-11, 2019 In The Yellow Bowl, claver, as in Tarclaver, Septemberclaver, and Anyaclaver, is used in the feudal sense of enclave (old French: enclaver; Latin: inclavare (to close with a key).

The "tar" in Tarclaver combines enclaver with TAR -- encountered as a UNIX archiving utility and later in my PARC-issued copy of Richard Stallman's legendary manual. (Richard Stallman, GNU Emacs Manual, 5th edition, October 1986). Because road metaphors permeate The Yellow Bowl, I also liked the connection of tar with asphalt. Contingently, John Updike's Tarbox was not on my mind at the time of naming Tarclaver. But a few weeks ago, I reread Couples -- not for the narrative but because I was interested in Updike's authorial reorientation of the town of Ipswich Massachusetts (about 30 miles North of Boston on the coast) into the fictional Tarbox, a town Updike described as being about 30 miles South of Boston on the Coast. At about the time that they moved to the marshlands of Labor-in-Vain Road, I lived on East Street, a few blocks from where the Updike family had lived prior to their move. Unlike place in The Yellow Bowl, there is little difference between Tarbox and Ipswich. Thus, in the rereading of Couples, instead of the intellectual exercise in creative place-shifting which I sought, I was thrown back in time to my house with its bookshelf-lined studio and etherial lilac hedge. In Updike's words: "Sometimes in these warm pale nights, as the air cooled and the cars on the road beyond the lilac hedge swished toward Nun’s Bay trailing a phosphorescence of radio music...." Ultimately, instead of exploring the differences between Tarbox and Ipswich (there weren't many), I moved on Google maps down East Street until I found the house I lived in with my then husband and our toddler-age son. The lilac hedge was gone; my vegetable garden was gone. An ugly driveway replaced the area where we planted an English garden. This week, I had already returned Couples to the library when I desired to read it again, not for the narrative (which doesn't wear well in this decade) but in search of descriptions of known place. It is not landscape that dominates this book by a man, whose wife at that time was a painter of landscapes. However, it is possible to look beyond Updikean misogyny and see the whole of Couples as a poetic blurring of women's bodies with place and landscape.

July 22, 2019

The 2019 The Yellow Bowl will premiere September 17-20 at HT2019, the 30th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media, held this year at the Institute of Information Systems in Hof, Germany. The exhibition is curated by Dene Grigar. Mark Bernstein is the chair of the creative track. In Hof, which is very close to the German-German border, in this year of the anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, in this year of the 30th anniversary of the WWW, HT2019 will focus on "Hypertext - Tear Down the Wall", with a goal of bringing different hypertext research directions and communities together. A creative track and a research track on "30 Years of Hypertext" are included in the program. Although the origins of my hypertextual authoring systems are documented in my 1991 Leonardo paper "Uncle Roger, an Online Narrabase" (submitted in 1989), how these systems have evolved in 33 years is of interest. I would have liked to write a paper on my narrabase and narrastruture authoring systems. But I was not able to do this and finish The Yellow Bowl in time to submit it to the ACM HT Jury.

Contingently I send thanks to Chris Klimas, the author of Twine, for his credit to Narrabase at this June's "NarraScope 2019 - Celebrating Narrative Games" conference, where he talked about the history of Twine in the context of HT authoring, saying: "By way of introduction, Twine is a decade old this year, which is a kind of milestone, especially for software, which often has a short life. That said, it exists in a broader context. Storyspace, the software that was used to create many hypertext works in the 90s, is now 32 years old. Judy Malloy, another early hypertext artist, has been working on her own system, Narrabase, since the 1980s. And Douglas Englebart’s 'mother of all demos', which was not where hypertext was invented but where it was introduced to a broader world, took place half a century ago now."

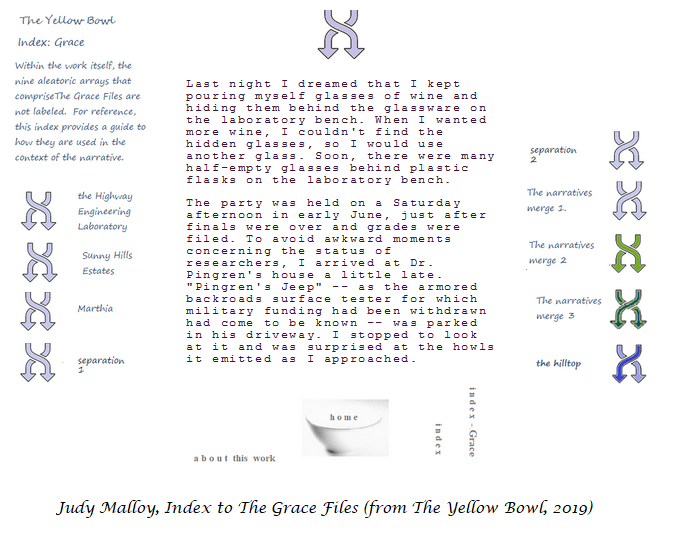

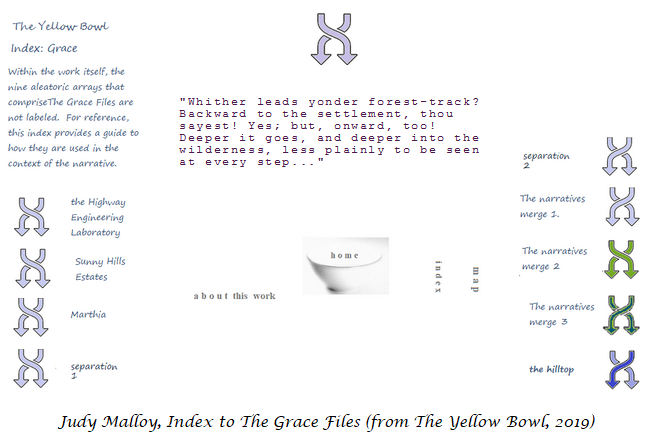

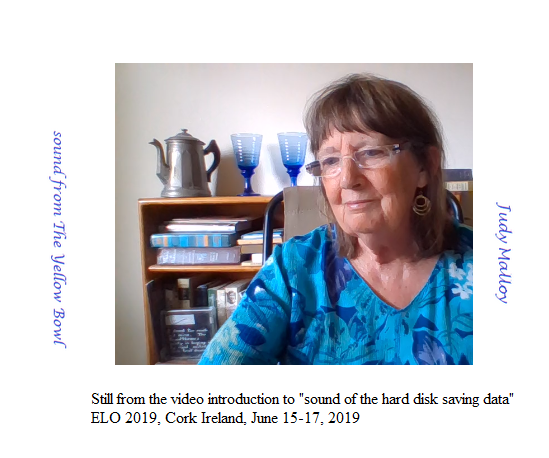

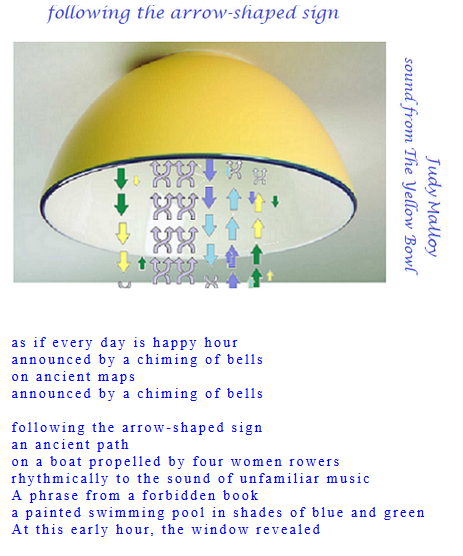

"Sound of the Hard Disk Saving Data", the transient electronic manuscript that was a part of the ELO Cork performance evening last week at the Kino in Cork Ireland, is the result of a struggle to convey a complex system in a poetry reading environment. It consists of seven polyphonic compositions that reflect my writer's memory of key passages in The Yellow Bowl. In each of these fleeting arrays, while words from The Yellow Bowl appear on the screen at random, layered recordings of my voice play in the background. I have found that when my own remixed words are encountered in their rightful places in the text of The Yellow Bowl, the experiences they key are heightened. Although these aleatoric songs are not precisely the same as the songs that Shakespeare inserted in both comedies and tragedies, I am experimenting with inserting output from "Sound of the Hard Disk Saving Data" directly into The Yellow Bowl, at the places where there is singing in the work itself. June 25, 2019 The question I asked when I began The Yellow Bowl 28 or so years ago was "What would happen if I wrote a work that had generative hypertext at its core, but the aleatoric texts were framed with sequential narrative?" At this time, I was interested in exploring literary possibilities at the conjunction of print and electronic literature. When I revisited The Yellow Bowl beginning in November of 2018, looking at the structure into which I had forced the narrative, I noted that it isn't until about the time when Helen leaves Anyaclaver and Clara leaves Installation Way, and the plot of the Helen/Clara stories intensifies/speeds up, that Grace herself begins to feel at home within the narrative. In the 2019 editing process, I wondered if I should rewrite the beginning so that the Helen/Clara stories and the Grace Files flow more smoothly together. No. Grace's initial struggle in the unaccustomed telling to her daughter a story of Grace's own devising creates an awkward tension that contributes to the creative satisfaction when -- at about the time the machines that pursue Helen sink into the swamp below Janet's cabin -- Grace begins to incorporate elements of the story into her own mental life. The writer of electronic literature works with both words and code. Contingently, in 1993, in studio testing and informal survey of colleagues, I found that readers were ignoring the randomly-generated Grace Files which are at the core of the narrative. They were only reading the sequential parts of the story! In response, after 10 lexias in the Helen and Clara stories were read, I (algorithmically) threw the reader into The Grace Files. There was of course an option to return to the Helen/Clara Stories.

In the 2019 reconstruction, I dealt with this issue by refreshing the Grace Files every 100 seconds; by fading in The Grace Files so that their presence is more noticeable; by making entry into The Grace Files a clear part of the interface choices for the Helen and Clara files; and by creating an index to The Grace Files which allows the reader to explore how they work within the narrative. My sense is that the index is most important in addressing this issue. It has also been useful to me in correlating the 9 arrays that comprise The Grace Files with the sequential Helen/Clara stories. My current position is that electronic literature can enhancce print literature -- and vice versa. In a 2017 electronicliteraturereview interview, I said: "...the boundaries are becoming somewhat blurred. Many of the strategies developed by writers of electronic literature can influence print literature and even in some cases have been utilized in print, while at the same time we see writers of electronic literature incorporating print components in their work. I have always believed that print literature is such a powerful interface that it will continue, but that electronic literature is equally powerful and will flourish and run side by side with print literature, so to speak. In the 21st century, the fact that electronic literature and print literature are each influencing each other is greatly enriching both fields!"

For example, recently reading Joyce Carol Oates' The Accursed (2013) I wondered if -- when Annabel, Oriana, and Todd emerge alive from their tomb and Josiah emerges alive from frozen hibernation -- Oates was echoing computer games, where in every playing the character you play may die, but in every replaying the character you play, having learned certain things to avoid (don't accept daffodils from a stranger), reenters alive. Yes, that can happen when you reread a book, but, perhaps because the player can alter the results, it is not as potent as when the reader assumes the character in a computer game. In the case of The Accursed, because this happens without rereading, as early twentieth Princeton becomes "the Great Underground Empire", the whole of the book could be read in the context of computer-mediated literature. But perhaps this is only my interpretation. It is always of interest to consider if a work of electronic literature could be effectively reproduced in print. Indeed, if we visit ancient manuscripts for Exodus 15 1-19, the three column structure of this extraordinary biblical text is clear. Thus, my use of the three column structure, which began in 1990, originated in print -- whether or not I knew this at the time of writing Thirty minutes in the Late Afternoon, and subsequently Wasting Time and The Yellow Bowl. June 12, 2019

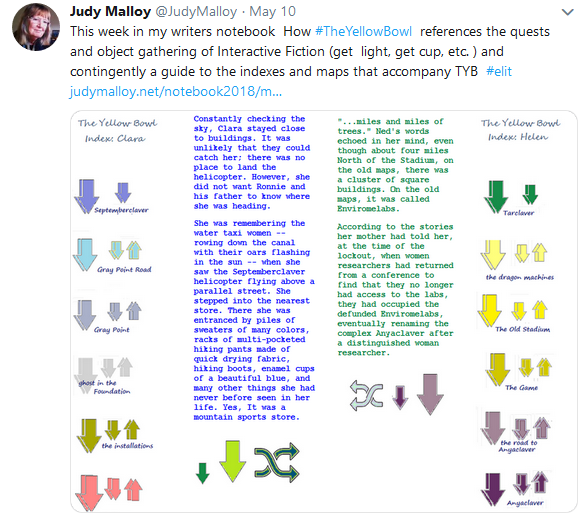

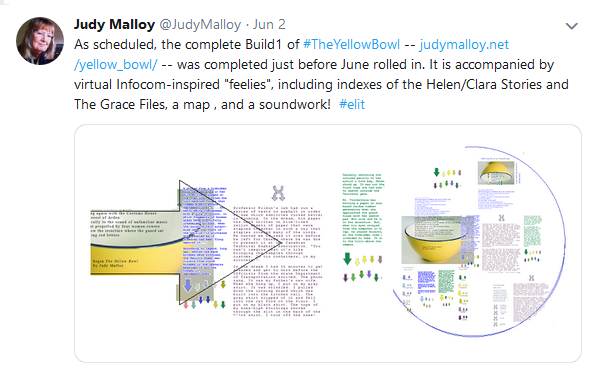

Build1 of The Yellow Bowl is completed! It should be noted that coming from a software background (in the distant past), I don't expect that a work based on code is ever finished. For better or worse, we are, for instance, up to Windows10; up to WordPress5.2; on the verge of IOS13. From my point of view, continuing to make my work accessible in fluctuating software/hardware environments is my responsibility. On the other hand, artists and writers generally reach a point where either, for our vision, a work is completed, or it is necessary to declare a work finished. Furthermore, at some point we will not be around to make sure that our works -- that bridge software and the creative arts -- continue to run. For my work, emulation would be the most appropriate. Restorative coding -- that preserved the original interface,/navigational structure and text -- might also be ok. The availability of retro-machines is enchanting, particularly in classroom systems, but retro-machines exist primarily in academic situations and thus provide only limited access. Meanwhile, for a living writer/coder, the struggle is to transmediate a work that doesn't run on contemporary platforms -- to transmediate it in a way that conveys the original but also -- taking into account our vision -- works on contemporary platforms. In the case of The Yellow Bowl, the existence of the numbered original text and the existence of my original BASIC software (which clearly showed how the software accessed the text) made it possible to create a DOSBox emulation of this work. However, because contemporary readers might not be able to negotiate a DOSBox emulated BASIC work that contained 800 lexias, I made the decision to transmediate rather than emulate this work. To do this, I used JavaScript in an HTML/CSS environment, and I designed an interface that both revealed the structure of the original work and provided indexes that made the whole of the content more accessible than it was in the original BASIC version. In the future, TYB could be transmediated again using the writing displayed in the indexes to the Helen and Clara Files; the writing displayed in the index to the Grace Files; the CSS animation that generates the Helen and Clara files; and the JavaScript code which generates The Grace Files. My writing in this notebook would also be helpful. Meanwhile, there is a satisfaction in "completing" the transmediation of a work of electronic literature with the depth of The Yellow Bowl. A few tweets that, based on notebook entries, briefly summarize the process of reconstructing TYB -- from November 15, 2018 to June 2, 2019 -- are reprinted below.

May 28, 2019

In an infosphere, where anyone/any entity can shout at us with unexpected autoplay of commercial messages, there are valid reasons for user choice as regards autoplay. However, when the process for allowing autoplay is difficult to access, the needs of art works are disregarded. Additionally, because this issue is complicated by rapidly changing browser autoplay policies, sound artists cannot be sure that what works today will work tomorrow. It should also be noted that some browsers whitelist big commercial entities; the statement by these browsers that autoplay is a bandwidth issue is disingenuous. From the point of view of artists and musicians, Microsoft Edge's current policy of allowing autoplay, while at the same time allowing users to disable autoplay is ideal. Firefox disables autoplay, but the process of allowing it is not difficult. But Chrome and Safari have been primary offenders in disallowing autoplay for sound. Programmatic work-arounds do work in some cases, but not in all cases. The bottom line is that as artists we cannot assume that autoplay will work. Even if autoplay can be enabled, we cannot assume that Internet audiences will know how to do this. Given this, and many other issues, we -- the art community -- can and should be calling for a browser that is designed specifically for viewing art works. Ideally this browser would work in tandem with another browser, so that audiences can move easily to the arts browser. Meanwhile, after much struggle, in the body of the work itself, I've removed the sound from The Yellow Bowl -- with the exception of the opening page, which will autoplay sound if a browser allows this, and with the exception of a filtered click icon on the second page which replays the same sound file. Then, instead of using the polyphonic sound which I envisioned as opening each section of the work, I created a separate sound work. Since I had originally conceived the sound as a component that reflected the polyphonic reading of the three sections of The Yellow Bowl, this is a workable solution. The sound wasn't necessary as part of the reading process itself. Indeed, when I resorted to installing click icons, they detracted from the reading experience. Instead, the new sound work associated with The Yellow Bowl provides a poetic listening experience that enhances the work. Importantly, although It is still necessary to enable autoplay to play the sound work, doing so does not detract from the reading of the work itself. A small amount of work -- on the interface and on the aleatoric database that generates text -- remains. May 10, 2019

The Yellow Bowl had lain dormant since its last showing at in 1995 (installed by the curator, Joseph DeLappe, in the exhibition Digital Identities at the University of Nevada's Sheppard Gallery). Thus, when on May 1, 2019, once again Helen and Clara met on a hill top in the woods east of the lake, The Yellow Bowl was reborn. The reconstruction work has been difficult, but I think it was worth it. The world model -- a world where women professors and researchers are shut out of their labs and in response set up an all women laboratory; where on campuses STEM pushes out the humanities; where communities are isolated by filter bubble electronic communication -- remains speculative fiction with disturbing contemporary resonance. But the difficulties two young women have in escaping male-dominated communities -- and their desire to explore the world outside of their isolated communities -- should not be challenging. Helen and Clara's dedication -- to the potential of the collaborative activist vision that guides their quest to find each other -- should not be looked at any differently than if they were young men with similar idealism and the strength and ingenuity to put it into practice. That a woman recently separated from her husband would tell this story to her daughter should not be surprising. And, 27 years later, I was pleased when I returned to TYB to observe that the role of fluctuating gender identity that pervades the narrative remains/is both contemporary and Shakespearean.

M eanwhile, back on the writing/coding front, since in the original version of The Yellow Bowl, it was possible to follow the Helen, Clara, and Grace narratives individually, an array of indexes that allow this access to the narrative have been created.

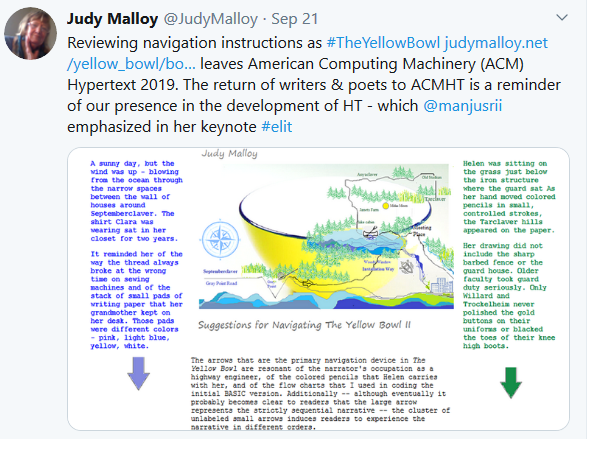

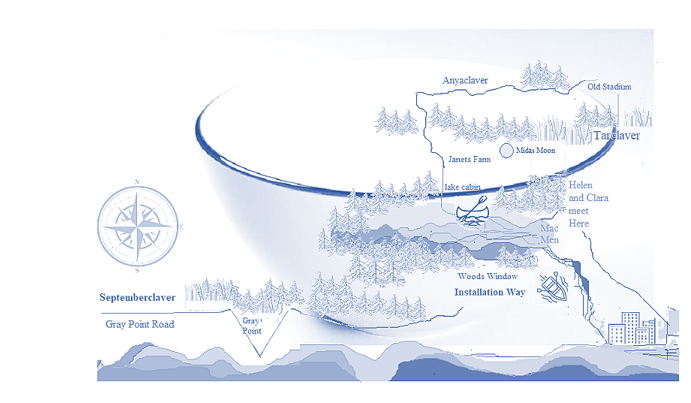

I envision a reader starting with the work itself at At some point, a reader of Helen and Clara's journeys might resort to the Index to the Helen/Clara stories Then, when Grace submerges as a result of imersion in the Helen/Clara stories, there is an "Index to The Grace Files" Additionally, at about the place where a reader is likely to need a map, on the interface, a link appears to a guide to navigation which contains a map A new version of the map will probably be created, and I'm still working on entering lexias in "The Grace Files". Also, issues with audio autoplay point to a need for a browser designed for the work of artists, writers, and musicians! April 25, 2019

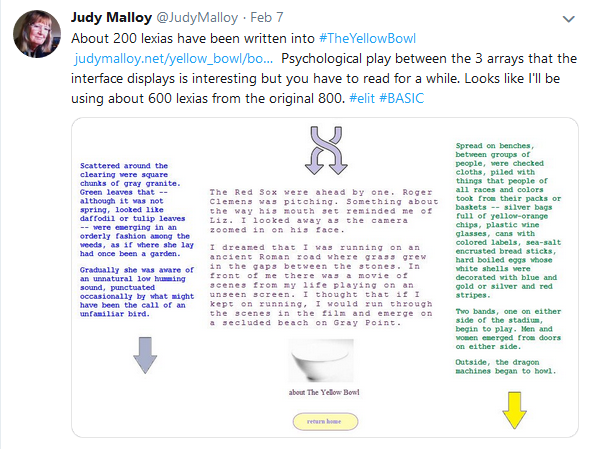

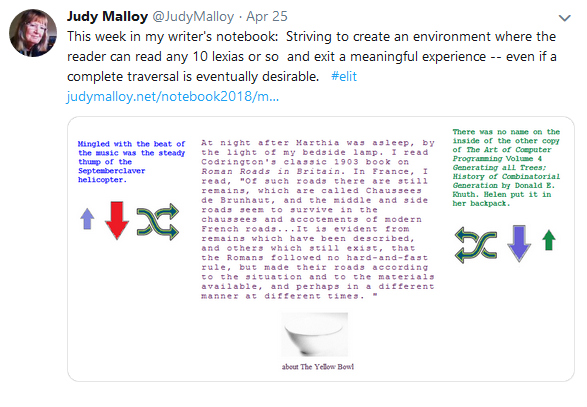

Work on The Yellow Bowl II, is coming to climax. Caught in the Helen-Clara stories (as is the narrator herself), these past few weeks, I have neglected "The Grace Files". However, extensive work on "The Grace Files" will soon commence. A primary issue in Internet-situated public electronic literature is how much of an in-depth work we expect a reader to traverse. Although we are not at a point of time where one practitioner speaks for all practitioners, every voice adds to our understanding of the writer-reader experience in electronic literature.

The 1992 BASIC version of The Yellow Bowl was not intended as an Internet-hosted work of electronic literature. Although when TYB was created (before widespread public use of the web), I had created UNIX-hosted electronic literature, TYB was originally under contract as an Eastgate stand-alone. Nevertheless, it should be noted that at that time, even Eastgate titles might not expect the amount of reading time that would be spent reading a print novel. Thus, in TYBII, the larger arrow suggests a preferred reading, but the multiple-arrow-navigation interface -- in tandem with various versions of the random icon that control the central text -- suggests that the reader is welcome to begin anywhere. This freedom from the tyranny of authorial control of reader experience is important in creating an environment where -- even if a complete traversal is eventually desirable -- a 10-lexia reader experience is viable.

April 10, 2019

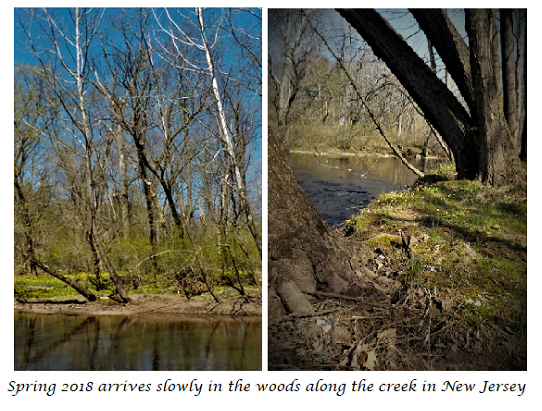

Early Spring in New Jersey, the woods are promising, and The Yellow Bowl II, heads into the home stretch. With Evie and Zoe's gift to Clara of a copy of As You Like It, in which the pages light up as they are encountered, leaving dark pages behind them, the themes -- of banishment/exile and subsequent fluctuating identity/gender identity in the Forest of Arden -- key Clara's journey through the lakeshore Forest. Some of this journey is in the Clara column. Additionally, a green-colored random icon leads to a set of "The Grace Files", where otherwise unseen aleatoric forest narratives reside. On the other side of this 3-column-structured data narrative data system, the toy baking soda and vinegar rocket that Helen gave Dr. Trockelheim is fitted with a guidance system. It lands at her feet, not far from the door of a farm built by an exiled artist. As is Grace, at this point, I, the real writer -- who has not revisited The Yellow Bowl since it was last shown in 1996 -- am deeply immersed in the story. Whatever the reception of The Yellow Bowl II, 27 years later, spending the time to reconstruct it has been worthwhile. Meanwhile (reading another writer's journey), in The Soul of a New Machine (Tracy Kidder, Boston/Toronto: Little Brown, 1981), I have returned to a world model where the chip wars, on which Uncle Roger centers, are replayed on another coast, where (as were the orchards of Silicon Valley), the forests west of Boston have been replaced with industrial parks. "Digital Equipment, Data General — there on the edge of the woods, those names seemed like prophecies to me, before I realized that the new order they implied had arrived already" (Kidder pp. 8-9).

The undercurrents of the environment Kidder describes are familiar:

" It was a gold rush. IBM set up two main divisions, each one representing the other’s main competition. Other companies did not have to invent competitors and did somewhat more of their contending externally. Some did sometimes use illicit tools. Currying favor, seeking big orders for chips, some salesmen of semiconductors, for instance, were known for whispering to one computer maker news about another computer maker’s latest unannounced product. Firms fought over patents, practices and employees, and once in a while someone would get caught stealing blueprints or other documents, and for these and other reasons computer companies often went to court... " (Kidder, p. 14-15) Yes, and the world model of Uncle Roger did not came primarily from my imagination. Uncle Roger is magic realism-infused historical fiction. In The Soul of a New Machine, Kidder relates that -- when Data General was initiating work on a new minicomputer in competition with DEC's (Digital Equipment Corporation) VAX -- Tom West, top hardware engineer at Data General, travelled to a City ("somewhere in America") entered a company, "as though he belonged there", and proceeded to a room where a new VAX had just been installed. A technician was there, but soon the technician left. In Tracy Kidder's words, here is what West did next: "Then West closed the door, went back across the room to the computer, which was now all but fully assembled, and began to take it apart. The cabinet he opened contained the VAX's Central Processing Unit, known as the CPU — the heart of the physical machine. In the VAX, twenty-seven printed-circuit boards, arranged like books on a shelf, made up this thing of things. West spent most of the rest of the morning pulling out boards; he'd examine each one, then put it back." (Kidder, p. 31) West also documented each chip -- noting the origins and types of all the chips and how many chips there were of each type.

Last night, at a time when -- in conjunction with the question "Who is the audience for Returning to The Yellow Bowl II, I observed that I had written a woman-centered story and had told the story in a way that focused on the divorced parent storyteller. It might have been of interest to write both the Helen and Clara stories as interactive fiction, but since my initial purpose was to combine sequential and random tracks, I did not do this. The temptation to eventually do this, is now difficult to evade. March 19-21, 2019

At this point in the reconstruction of The Yellow Bowl, the place has been reached where Grace more centrally assumes the role of storyteller, and the journeys of Helen and Clara begin to merge with "The Grace Files" -- not only Grace's observations about the story, but also (because Marthia is not interested in long passages describing scenery) sometimes words from The Scarlet Letter that concern the forest, or road materials passages from back issues of Good Roads, or references to the Yellow Brick Road from The Wizard of Oz seep into the "Grace Files".

Marginalia: The Wizard of Oz (1900) was written at a time when brick roads (invented by Mordecai Levi in West Virginia in 1870) were gaining favor. If The Yellow Bowl had been written in the 21st century, in "The Grace Files", Grace might have observed a resurgence of interest in brick roads, but in 1992, brick roads were probably not of much interest to her Highway Engineering Department.

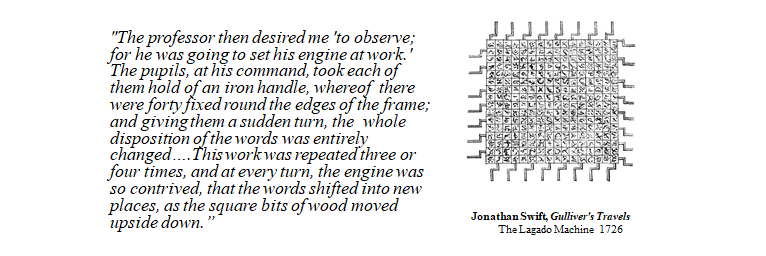

Other potential anachronisms surface and resurface when a writer/coder is reconstructing a narrative written 27 years ago. For instance, as Clara approaches the Woods Window, she encounters a room where 20 rectangles are projected on the wall. Each rectangle contains constantly changing passages that the inhabitants of this room enter from books. Since The Yellow Bowl was written before the web, the common form of remix, that was ushered in with the web had not yet occurred. Some of the language that I used to describe this room is reminiscent of Swift's description of the Lagado Machine in Gulliver's Travels. I may have seen Jackson Mac Low's sexist print remix of Virginia Woolf's The Waves ("Ridiculous__ in Piccadilly", 1985). I was not aware of Olivier Auber's image- based Poietic Generator. I think that with the Lagado Machine in mind, I was using the generative hypertext of "Terminals" and Penelope and the potentially movable squares of text that I painted for the wall of my 1989 installation of its name was Penelope. Whatever my sources were, in The Yellow Bowl, the wall of generative words that Clara encounters, is clearly meant as a literary remix reflection on her future routes. It also marks the point where the generative hypertext of "The Grace Files" spills into the stories that Grace tells her daughter, and vice-versa. Nevertheless, when I revisited this room 27 years later, I was surprised. Marginalia: Last night, while contemplating these issues, I was reading Joyce Carol Oates' The Accursed, which I bought at the Bryn Mawr-Wellesley Book Sale, along with Tracy Kidder's The Soul of a New Machine, Tom Standage's The Victorian Internet, and 50 Hikes in New Jersey.

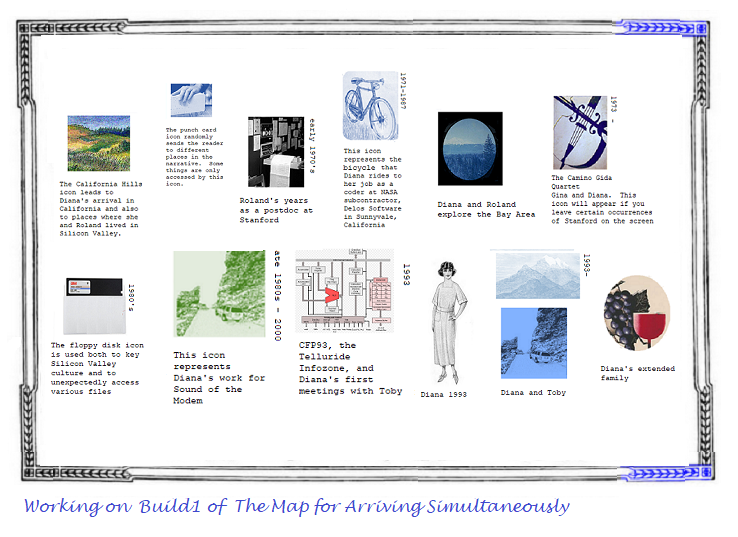

C ontingently, I'm pretty sure that when The Yellow Bowl began, I made a map of the routes that Helen and Clara would follow on their journeys. However, no TYB map is in my files. So, last week, I re-mapped their routes. The map I made is probably not visually appropriate for inclusion in the work itself, but I enjoyed making it, and it simplifies the task of creating a new map to include with The Yellow Bowl.

March 1, 2019 Just as what is in "The Grace Files" is not on the surface the inspiration for the Helen and Clara Files, what was happening in my own life at the time had little surface relationship to "The Grace Files" that form the central tract of The Yellow Bowl. ["The Custom-House":] At the time of the beginning of The Yellow Bowl, my son was away from Berkeley for the first time, spending his junior Cal year at the University of Sussex in England. Previously in Berkeley, to support my household and my work as an artist/writer, I had been working with information and library systems. However, in 1992 I had chosen to quit the two East Bay library jobs I had -- keeping only a third job as a Leonardo and Leonardo Electronic News Associate/Coordinating Editor, as well as the publication process of its name was Penelope, which was under contract to Eastgate. -- and move to New Hampshire to spend a year with my mother, and focus on my own work (For spare change, I also kept an indexing contract with the Annual Reviews). The subtle ways these life altering changes seeped into The Yellow Bowl were not as apparent to me then as they are now. Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that The Yellow Bowl is entirely fiction.

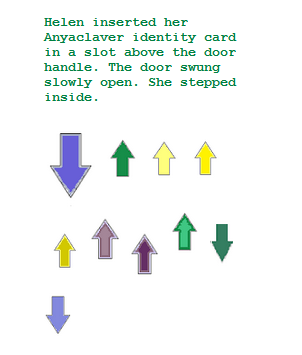

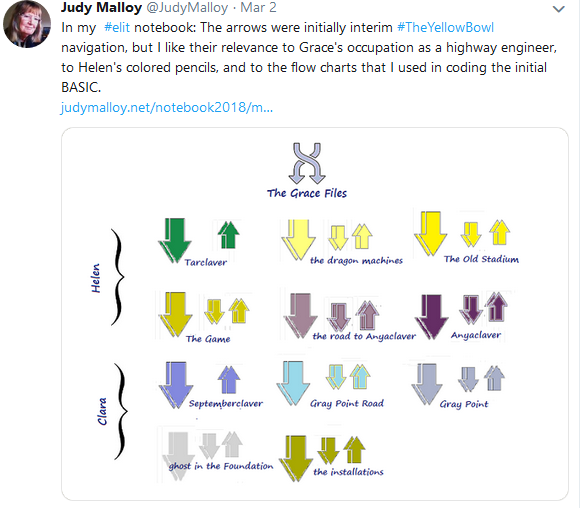

Now (over 25 years later in 2019) it is time to confront the possible permanence of the interim navigation system -- the arrows of many colors -- that I have been using as the re-coding of The Yellow Bowl progresses. During the re-coding process, I elected to work primarily on the global interface and on entering the text. The navigation system, envisioned as an audio index, would be created when the task of entering the text was completed. There were several reasons for this: 1. There are only a few copies of the text extant. 2. I anticipated that I would be doing some editing and rewriting as I entered the words, and that at least 200 lexias would be eliminated -- a process that could alter the navigation details. Although the navigation arrows were intended to be an interim device, as the work progressed, I became attached to their relevance to Grace's occupation as a highway engineer, to the colored pencils that Helen carries with her, and to the flow charts that I used in coding the initial BASIC. Additionally -- although eventually it probably becomes clear to readers that the large arrow represents the strictly sequential narrative -- the cluster of unlabeled arrows induces readers to experience the narrative in different orders. This implied but not suggested reading experience also characterized the original BASIC version. I am currently inclined to include the arrows as a part of the final interface. If this occurs, for those who like maps in works of hypertext literature or Interactive fiction, a map will be included in the documentation that will accompany the final work. March 2: It should be noted that currently the visually satisfying masses of many arrows only occur on a few selected screens. This is because as the work grows, each clump of arrows changes and new arrows need to be regularly added. Since this takes time, clumps of arrows throughout the work will probably not appear until the writing is completed. February 17, 2019

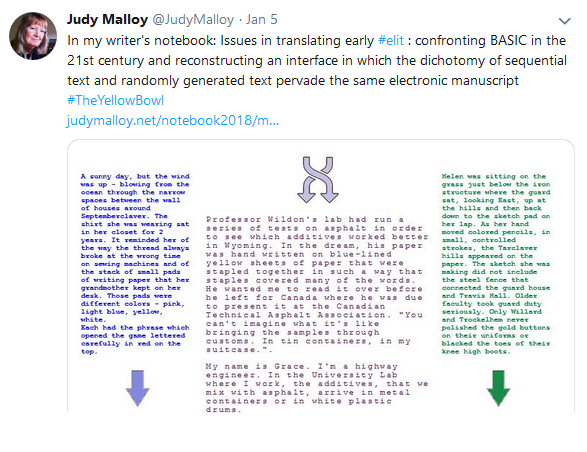

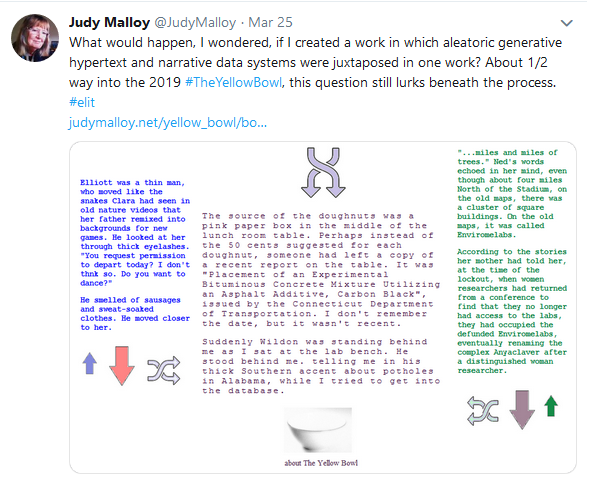

T he translation of the 1992-1993 The Yellow Bowl from BASIC into a JavaScript HTML5/CSS environment is one of the most interesting projects I have ever undertaken. Partially, this is because -- while my usual way of working is to begin with content, envision a system for that content, and then create the work by composing and coding somewhat simultaneously -- for The Yellow Bowl, I began with a system that I wished to explore. Partially, this is also because when I wrote The Yellow Bowl, my life was in transition and yet at the time I did not realize how much this drove what became the content of the work. Thus, this translation is a personal journey into a writing past that was forgotten in the wake of a life-altering accident. As regards the authoring system, in 1992, with three-column systems, I had recently created two works -- Thirty Minutes in the Late Afternoon and Wasting Time. Both of these works could be considered polyphonic narrative data structures, -- as opposed to the aleatoric generative hypertext with which its name was Penelope was written. What would happen, I wondered, if I created a work in which aleatoric generative hypertext and narrative data systems were juxtaposed in one work? A little more than 1/4 into the 2019 Yellow Bowl, this question still lurks beneath the process. The primary narrative issues in The Yellow Bowl are not what happens in the two stories Grace tells her daughter. They are who Grace is and what is the future of her relationship with her husband Wesley (from whom she is separated when The Yellow Bowl takes place). On one level, the narrative is informed by how Grace alters her own experience (as set force in the central aleatoric "Grace Files") to create the Helen and Clara stories. On a more submerged level, the narrative is informed by what Grace does not tell us about her own experience that might have informed the narratives she tells her daughter. Within the "Grace Files", these issues are keyed by a series of passages that Grace quotes from Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter. For example: "...the floor of our familiar room has become a neutral territory, somewhere between the real world and fairy-land, where the Actual and the Imaginary may meet, and each imbue itself with the nature of the other." Or "It was a folly with the materiality of this daily life pressing so intrusively upon me, to attempt to fling myself back into another age, or to insist on creating the semblance of a world out of airy matter, when, at every moment, the impalpable beauty of my soap-bubble was broken by the rude contact of some actual circumstance." As I work on The Yellow Bowl, in my mind I replay the theory and practice of hypertext literature in the early 1990s. For instance, the impact of what the reader sees or does not see in a traversal plays a strong part in its name was Penelope, in Michael Joyce's afternoon, and in Stuart Moulthrop's Victory Garden. In The Yellow Bowl, the passage below is a variable in the aleatoric Grace Files. In looking at the relationship between Grace and Wesley, this is an important passage. But whether the reader sees it or not is a question of chance:

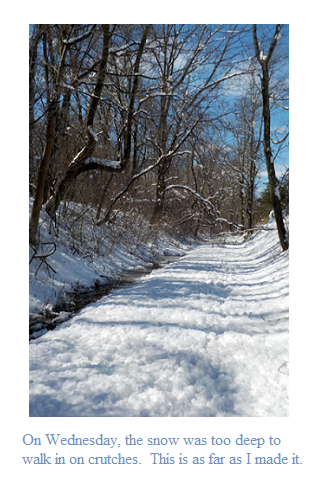

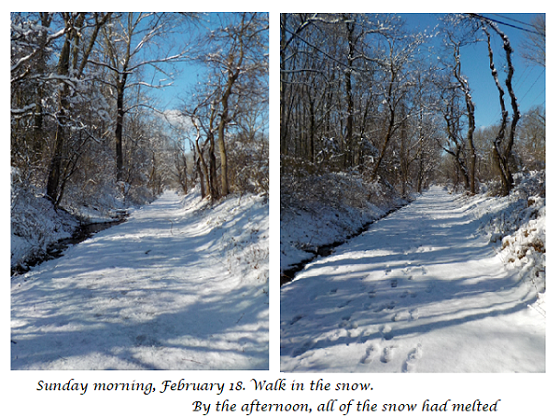

"It was no different than my occasional trips with male colleagues to cold Northern places where the highways deteriorated in the winter, I thought, looking down at the cold sea beneath the pier, remembering a snowy January night in Wyoming. He was a tall blond highway engineer with a cabin not far from the test site. We were snowbound, drinking cheap Canadian rum." For instance, as the animated text moves across the screen, I am constantly reminded of an at-that-time often-quoted passage in Joyce's Of Two Minds: "Print stays itself; electronic text replaces itself. If with the book we are always printing -- always opening another text unreasonably composed of the same gestures -- with electronic text we are always painting, each screen unreasonably washing away what was and replacing it with itself." (p 186) January 26, 2019 M uch has happened since the first bars of The Yellow Bowl were posted three weeks ago. I suppose a reader of this notebook might assume that I had been on many adventures. Well yeah, I walked through the woods after a snowstorm; family came for a cheerful visit; a flock of seemingly hundreds of wild geese settled on a hillside where I was walking; I got a new ski hat and a wonderful sweater for my birthday; I'm reading/rereading Hawthorne's 1850 The Scarlet Letter, Thomas Codrington's classic 1903 book on Roman Roads in Britain and Rob Gehl's 2018 Weaving the Dark Web; much pleasurable time has been spent documenting the panel and work from my SAIC ATS Social Media Narratives course; and many mornings I got up early to watch the FIS World Cup races with my NBC Snow Pass.

Usually when beginning a new work of electronic literature, there is a struggle with the code, coupled with a slow process of becoming a new narrator. In the past when I returned Uncle Roger and its name was Penelope to the original BASIC in which they were first written, it was mainly a question of remembering old code. Otherwise, Uncle Roger and its name was Penelope are works had stayed with me in various forms. Returning to The Yellow Bowl has been a very different experience. In the files of material related to The Yellow Bowl I was shocked to find a copy of the publication contract for TYB that I had signed with Eastgate. It was dated June 9, 1994, exactly one month before I was run down in a crosswalk on July 9, 1994. TYB is a difficult work in many ways; a work that was hard to return to at a time when I felt my life was shattered. So, when Mark Bernstein suggested that instead Eastgate publish Forward Anywhere, the work that Cathy Marshall and I wrote under the auspices of Xerox PARC, of course I agreed. In 1995, Joseph DeLappe kindly installed the BASIC version of TYB in Digital Identities at the University of Nevada's Sheppard Gallery. And then TYB fell by the wayside as Arts Wire migrated to the Web; I assumed editorship of Arts Wire/NYFA Current; and my work slipped onto the Web with name is scibe, L0veOne, and The Roar of Destiny. It has been a long time since I was immersed in The Yellow Bowl, and I am not yet sure where it fits in my work. At the moment it is interesting -- like a treasured lost earring finally found under the bed or a 1903 book on Roman highways, or a music box that plays "over the hills and far away to Grandmother's house we go". S ince at this time it seems most important to continue entering text in TYB, to document this process what follows are only very brief notes. __the goal of retaining only about 400 lexias -- out of the original 800 lexias -- is so far strengthening the work. __A few new lexias have been written. For instance, the information about 3-part Roman Highways was not in the original work.

__I anticipate the whole will need to be copy-edited when the text is all in. __In the original work, Grace's reading of The Scarlet Letter functions as a reminder of her outsider status -- as a woman Highway Engineer and as a single parent. There are always surprises when one rereads Hawthorne's splendid work. January 4, 2019

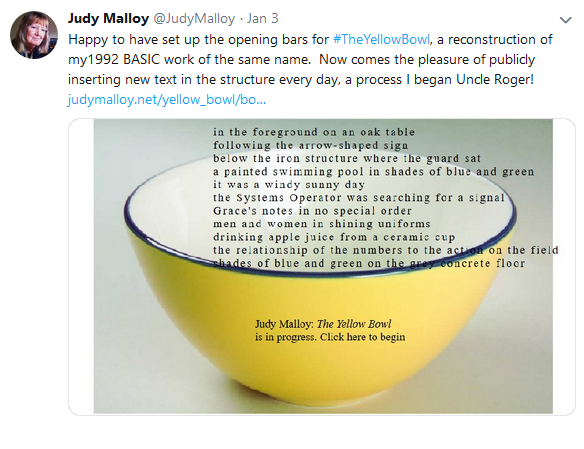

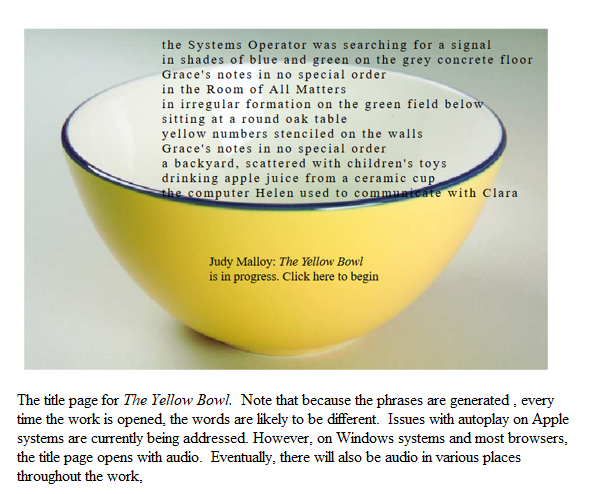

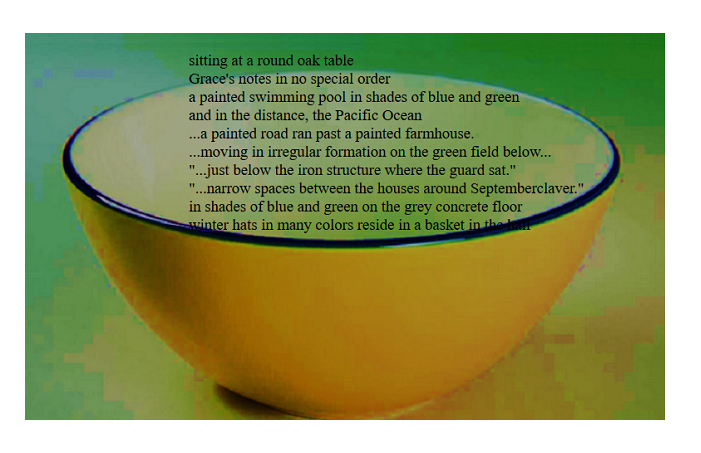

The first bars of The Yellow Bowl were posted this week at http://www.judymalloy.net/yellow_bowl/bowl_titlepage.html A few changes have been made, but as I begin to enter selected lexias from the 800 lexias that comprised the original I am very happy with how it is working. Once you enter the body of the work, the interface now looks like this:

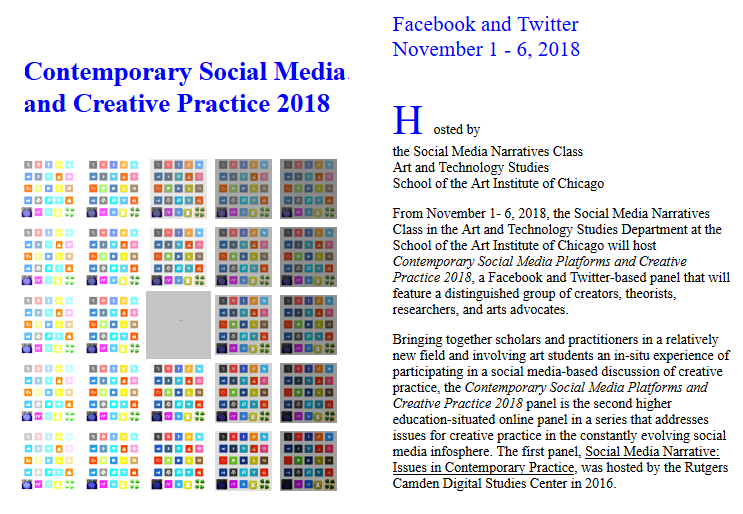

Although it is not precisely equivalent to the original BASIC interface and structure, a clarity that resonates with the original has been retained, as have the issues with which I began in circa 1992 -- how writers of fiction distort the events of their lives and how a dichotomy of sequential text and randomly generated text can pervade a computer-mediated narrative. In the center, the traditional icon for "random" produces The Grace Files. On either side, an arrow, a symbol for proceed forward, produces the sequential stories that Grace tells her daughter. The themes of the whole: separation -- and a subterranean theme of male power in technology-centered places -- are reflected not only in The Grace Files but also in the stories Grace tells about two young women, who escape from magic realistic male-centered colonies and embark on a perilous search for each other. Years ago, when I composed The Yellow Bowl in the time immediately before the public arrival of the World Wide Web, I was exploring the potential of code and computer display systems to shape word-based narrative experience. Thus, although there will eventually be audio throughout The Yellow Bowl (there was some sound in the early versions), I have elected to retain the prominence of written words in this reconstruction of the last work that I wrote in BASIC. Now, as every day I add a few more lexias, it is a pleasure to see this work emerge! December 20, 2018 Grading Week Interlude: A t this time of the year, when final projects arrive just before Christmas, it is as if I put up a stocking, and suddenly it is full of digital projects I have only dreamed of exploring. This year, my Social Media Narratives students in the Art and Technology Studies Department of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) explored the potential of social media-based creative practice in a range of extraordinary creative works that used social media: ___as a tool/resource to create content for physical works, such as a graphic narrative/artists book created with images of artist-made Second Life avatars and tableaus; such as an artists book in the form of an eBay artist's wish list that -- distributed as mail art -- echoed eBay's dual online/offline process; such as an installation based on a work of YouTube self-documentation that was challenged with 78 copyright notices. ___and/or social media as a host for in depth electronic literature, such as a poetic Instagram-based series of explorations of post-colonial Mexicanx identity; such as the use of Facebook as a "flux box" container of media that discloses narrative in different ways; such as a Twitter-based narrative that challenges the reader to decipher identity as expressed only in a binary number sequences; such as a Twitter-based multi-identity narrative data structure -- that explores issues that might arise in a speculative quantum physics-based universe where multiple versions of oneself exist. ___ and/or invigorating "traditional" approaches social media creative practice, with works such as photoshopped malleable gender selfies; the blog as an extension of a performance art persona; a YouTube playlist that is also a poem created with the titles of a narrative-rich series of found videos; and a photography student's food page that -- using photos of her original recipes, interspersed with photos of restaurant fare -- promotes a vegetarian lifestyle. ___and/or Art as Research explorations of social media platforms; such as how the Facebook interface has limited the shaping of identity; and conversely, such as how groups of artists are creating visual coherency on Instagram; ___and/or new approaches to online community, such as designing, organizing, creating and hosting a lively Instagram-based archive of non-binary identity.. Detailed information about the work each SAIC student created will be published in content | code | process (probably in February 2019) in conjunction with the documentation of Contemporary Social Media Platforms and Creative Practice 2018, the online panel the SAIC ARTTECH class hosted in November, that in addition to contemporary creative practice on social media, looked at the impact on the arts of ethics and surveillance problems issues with commercial social media platforms

-- with panelists including Kathi Inman Berens, Asst Professor, Digital Humanities and Publishing, Portland State University; Joy Garnett, Arts Advocacy Program, National Coalition Against Censorship; Robert Gehl, Associate Professor, Communication, University of Utah, author of Reverse Engineering Social Media: Software, Culture, and Political Economy in New Media Capitalism; Ben Grosser, Asst Professor, New Media, School of Art + Design, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; Juana Guzman, former Vice President of the National Museum of Mexican Art; and Gary O. Larson, formerly writer for the National Endowment for the Arts and the Center for Digital Democracy. The whole will be the part of a series on social media creative practice that began with a panel hosted by the Rutgers Camden Digital Studies Center in 2016.

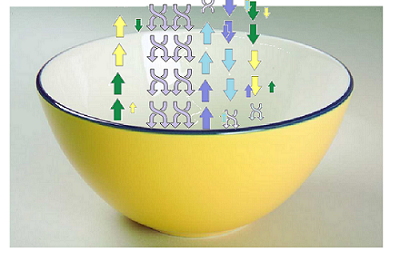

December 4, 2018 S truggles with the new The Yellow Bowl interface have dominated the past two writing/coding weeks. After toying with an icon-based interface somewhat like that used in Arriving Simultaneously, finally, an interface that works emerged. As a titlepage, I am using an animated image of text moving in a yellow bowl. Within the body of the work, animated text will be used as images for the Grace, Helen, and Clara files, and when index phrases are hovered on, spoken word sound that keys a new part of the story will emerge.

"The congruence in my work of poetry, information, and visual art stems from the 'eruption of language in the field of visual arts' in the 1960's and 70's when John Baldassari, Lew Thomas, Alexis Smith, Ed Rusha, Ben Vautier, John Cage, Alison Knowles, Laurie Anderson, Arakawa, Joseph Beuys, Hans Haacke, and others (bred on Jack Burnham and Rosalind Krauss, on Douglas Davis, on Joseph Kosuth's "Art After Philosophy") began making art in which *word* based criticism, and/or philosophy, and/or process *was* the work."

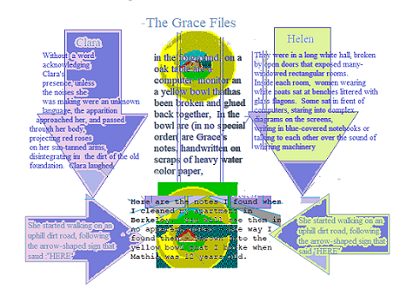

3. When I attempted to use the interface for Arriving Simultaneously as a starting point for The Yellow Bowl, I realized how integral the Arriving Simultaneously interface is to Diana's story, and I did not want to steal her interface for another story. Three-column interfaces: In 1990, I used a three-column textual interface in Thirty Minutes in the Late Afternoon, a narrative data structure, derived in part from the wooden text sculptures I was making in my studio at that time. Not much later, I used an animated three-column interface in another narrative data structure, Wasting Time. In all these works, the columns were visible to the reader/viewer. In contrast, the original structure of The Yellow Bowl (described in detail in my last entry in this notebook) used a "concealed" 3-column interface. The new version of The Yellow Bowl presents the multi-column structure in an interface where it is partially visible to the reader. I say partially because to keep the screen size workable on iPads, it was not possible on one manuscript screen to adequately display the two stories, and the Grace files, and the hypertextual sound index. At this point, the most elegant solution, as depicted in the figures above, is on one screen to display one narrative (Helen or Clara), plus a central aleatoric (never the same) section of the memory-based Grace files, plus the hover-sound index. For the reader, who can decide when to move between the Helen and Clara stories, this structure retains the original element of mystery that accompanies the game-like progress of the parallel stories of Helen and Clara -- who will eventually meet, walking up a hill on opposite sides. What I like about this interface is that it retains some of the look and feel of my work in the preweb early 1990's, while at the same time, it is sufficiently "classic" to resonate in the 21st century. November 14, 2018

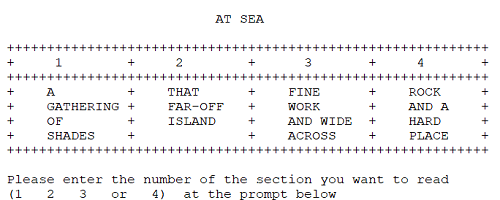

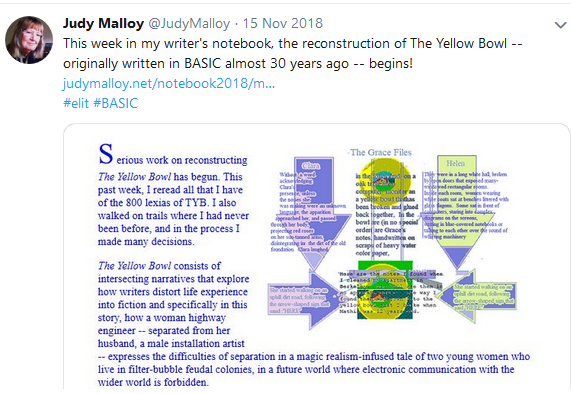

The Yellow Bowl consists of intersecting narratives that explore how writers distort life experience into fiction and specifically in this story, how a woman highway engineer -- separated from her husband, a male installation artist -- expresses the difficulties of separation in a magic realism-infused tale of two young women who live in filter-bubble feudal colonies, in a future world where electronic communication with the wider world is forbidden. Male professors have seized control of the University-centered Tarclaver where Helen resides. Robotic dinosaurs chase the women who escape from Tarclaver. At lunch hour in Septemberclaver, everyone plays the same video game. The City of the Rusted Truck, where Clara is held captive after she escapes from Septemberclaver, is a warren of abandoned artists' installations. In Anaclaver, where Helen is held captive after she escapes from Tarclaver, computers are outlawed, and the inhabitants only read books. Macmen, who only communicate with icons, hunt for Clara on a swamp-surrounded backroad. The narratives that Grace tells her daughter Marthia are richly detailed. They are informed not only by her separation from Wesley, but also by radically changing computer culture in the early 1990's when they were written. However, almost 30 years later, my judgement is that The Yellow Bowl will work most effectively as one magic realism-infused dynamic manuscript. In the translation process, approximately 400 lexias will be cut from this work. In the original BASIC version -- possibly the most complex work of fiction ever written in BASIC -- the reader moves between the randomly produced "real" events that inform the Helen and Clara fictions and these fictions themselves, which relate how Helen and Clara discover each other's existence using communications software on old computers; escape from guarded enclaves; and, to find each other, embark on separate perilous journeys. The "real events: (the Grace files) reveal incidents in Grace's life that in surprising ways inform the story she tells. In the original version, the reader selects which part of the story to enter. Only one part of the story is displayed on the screen at one time, but it is always possible to move between narratives.

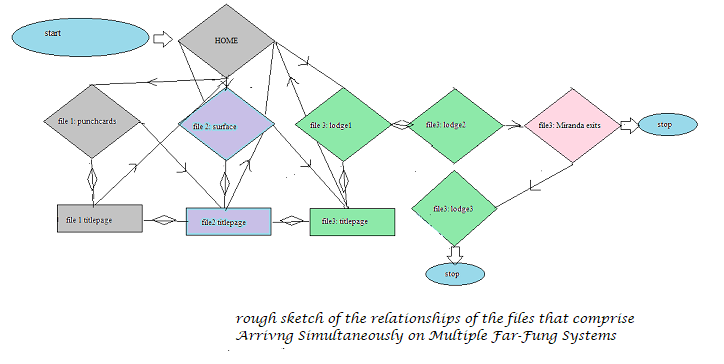

The 1990-1993 version, including the original BASIC program, exists in various archives, so it will not be lost. My current thinking is to re-structure the work in a dynamic electronic manuscript where the aleatoric Grace Files will reside in the center -- flanked on either side by segments from the Clara and Helen stories (told sequentially in short lexias with filmic jumps). In the original version, just before Clara and Helen finally meet, Grace's estranged husband, Wesley, concludes the story. In the new version, there is will be stronger indications that this unlikely couple, the highway engineer, Grace, and the installation artist, Wesley, will reconcile. October 27, 2018 A mong the last additions that I made to Arriving Simultaneously on Multiple Far-Flung Systems was A FORTRAN Coloring Book (by Roger Kaufman, MIT Press, 1978). Although 40 years later in 2018, some of the text of this remarkable tutorial seems mildly sexist, A FORTRAN Coloring Book -- in which many secrets of FORTRAN are explained in detail -- provides a memorable learning experience. The entire book is hand-written and illustrated by Kaufman, who (among other degress) holds an MFA from the Yale University School of Drama, Department of Theatre Engineering.

Also in recent variables were the names of some of the women who worked for Ball Aerospace on the Deep Impact Mission. Although I knew their names from Todd Neff's From Jars to the Stars: How Ball Came to Build a Comet-Hunting Machine, among other sources. it was necessary to work from what Diana might possibly know in 2006. The only mention of Amy Walsh I could find in that era was in a 2005 issue of the newspaper of her hometown, Steamboat Springs, Colorado: Former Local Student Engineer for NASA Project. Ultimately I decided that -- because he was still doing contract work on legacy FORTRAN for NASA contractors, where this information might be available -- Monty, whose memory was legendary, might have seen internal reports on Deep Impact.

"...what the poem amounts to if carried out too far, is an eternal project, and for most of us eternity is more time than we have at our disposal for perfecting works of art" - Emmett Williams W hen I featured Emmett Williams' IBM this week on the home page of Week 9: Generative Strategies of my SAIC Social Media Narratives Class, in my own work, I had already made the decision that it was time to stop writing and editing Arriving Simultaneously on Multiple Far-Flung Systems. October 2-3, 2018

Interesting, innovative, and surprising work is emerging from the art students in my School of the Art Institute of Chicago virtual-studio class on Social Media Narratives. And suddenly life seems better. Or did until the wind began to howl, and it began to rain, so loudly that it sounded like Niagara Falls. And I realized that I still had edits to respond to on a paper, had not yet updated content | code |contents, and an update to this writer's notebook was due. Yes, it is a self-imposed deadline, but my notebook drives my work, and it is thanks to the keeping of this notebook that even in the busy first week of a new semester, work has continued on the preparation of Arriving Simultaneously on Multiple Far-Flung Systems for a search for publication. E diting Electronic literature. A spell check was initially done on all the arrays that comprise Arriving Simultaneously on Multiple Far-Flung Systems. However, last minute edits resulted in mistakes that were unseen when the work was randomly generated. In order to facilitate spell checking, I made a few temporary changes in the code, so that the complete text (without code) could be printed out and subsequently submitted to a spell checker. (platfrm, minature, the the, momment, muntains, opportunites, from from, univited, unxpected, been been, flickerered, comferencing, on on, orginally, and there were more...)

Hopefully, I caught all of these, but there is always the possibility that further mistakes were made in the replacement process. Editing electronic literature can be

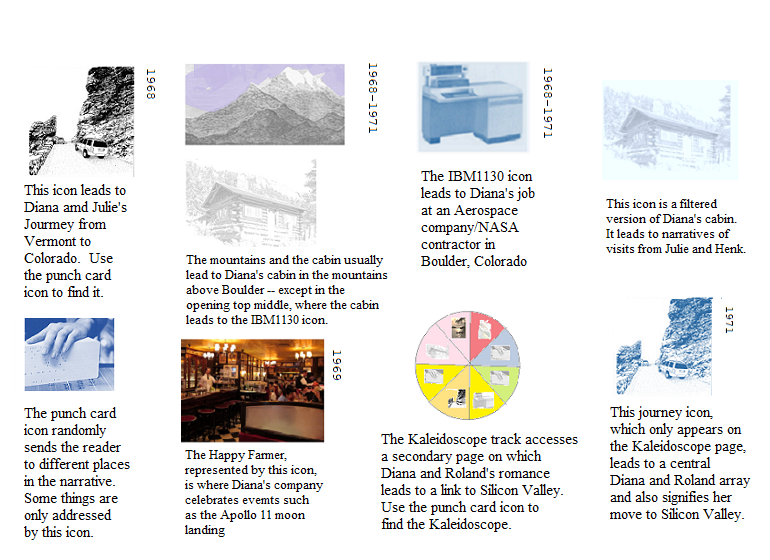

T hen, I plunged into the retooling of the page that the kaleidoscope icon generates on the opening page of when the punch cards were placed in the punch card hopper (File 1 of Arriving Simultaneously),

In contemporary society, a woman with a job as important as Diana's job was would not be as likely to immediately relocate to the state where her fiance worked, but this story takes place in 1971, when Diana's immediate move was more expected. Perhaps there was a reconsideration of my own life when initially I put Diana and Roland's romance on the side of the kaleidoscope -accessed page, instead of in the center of the page where it belonged -- and where it now resides. However, If you never click on the kaleidoscpe icon (or on "what?") Diana will remain in Colorado and never go to Silicon Valley.

E lectronic Literature is not a physical book. In a print book, you can tell from the thickness of the volume what percent of the book you have read and what percent remains. Although there are ways to include this information in the interface, a writer of electronic literature might instead play to the affordances of hidden content that computer-mediated interfaces offer.

_______________________________ September 14-15, 2018 As background for new material inserted in Arriving Simultaneously on Multiple Far-Flung Systems, in the end of August and the beginning of September I watched a movie I had never before watched, Apollo 13 (1995); read The Life and Death of a Satellite by Alfred Bester (Little, Brown, 1966). In the Congressional Record (April 26, 2005) and in several NASA Technical reports (Hamer and Johnson, 1970,1971), I found background information relating to Katherine Johnson's role in the return of Apollo 13; and I read the wonderful 2018 children's book, Counting on Katherine: How Katherine Johnson Saved Apollo 13 (by Helaine Becker; illus, Dow Phumiruk). From these and other sources, in this time period, new variables were added to Arriving Simultaneously:

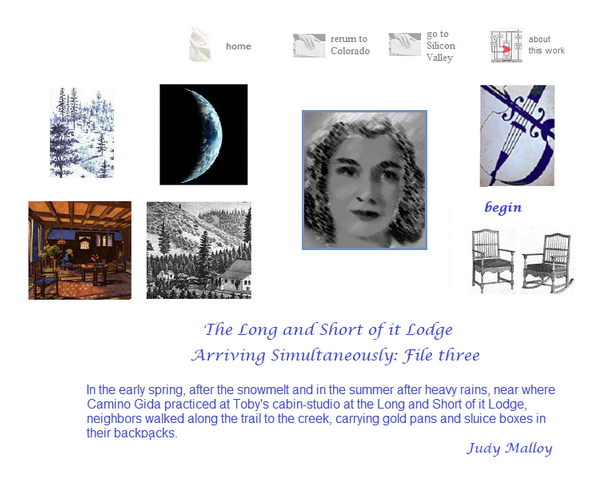

1. In Arriving Simultaneously, the tense atmosphere in the aerospace community during the troubled return of Apollo 13 is not considered until the end of August, 2018. This was the first time in my life that I watched the movie, Apollo 13 ; watching it exhumed stressful memories. In response, this variable was added to The Long and Short of it Lodge, file 3 of Arriving Simultaneously: "The missing recollection in my mind -- of when on April 13, 1970, an oxygen tank explosion aboard Apollo 13 sent mission control and the three astronauts into a nightmare of difficult return -- was not acknowledged until I left the room when Toby played the video of Apollo 13. I think it was because in April 1970, the atmosphere of worry and gloom was so pervasive that even the magic of the return of the astronauts could not dispel the ghosts of the men who died at Cape Canaveral, six years earlier."

2. Katherine Johnson, whose calculations were reportedly instrumental in the return of Apollo 13, is absent in the film, as is Margaret Hamilton, who was lead Software engineer for the Apollo program. Since Margaret is already mentioned by name in Arriving Simultaneously, Katherine was of primarily importance. But how her calculations were implemented in the Apollo 13 return is often offically ignored. Because I'm working in a time frame that does not go beyond 2006, I looked at the words of Texas Congresswoman Eddie Bernice Johnson, on the floor of Congress in 2005, when she introduced a resolution "Recognizing the Significance of African American Women in the United States Scientific Community." She said: "In the field of space exploration, while most are familiar with Dr. Mae Jemison, few are aware that Katherine Coleman Goble Johnson was a key member of the control room during the Apollo 13 crisis. Katherine Johnson, a physicist, space scientist and mathematician, was instrumental in formulating calculations that helped the Apollo 13 return home safely in 1970 after a fuel tank explosion and computer system failure." In potential support of Katherine Johnson's role, these two NASA Technical Reports, published soon after Apollo 13, are also of interest: __Harold A. Hamer and Katherine G. Johnson, An Approach Guidance Method Using Single Onboard Optical Measurement", NASA Langley Research Center, NASA-TN-D-5963, 1970. From the conclusions: A method for determination of approach-velocity corrections for a space vehicle has been presented. The method has been applied to the approach phase of earth-moon trajectories; however, it will also apply to reentry control for moon-earth trajectories. The method is unique in that only a single onboard position measurement is required to determine the guidance correction for controlling the perilune-radius magnitude..." (p.22) __Harold A. Hamer and Katherine G. Johnson, "Midcourse And Approach Guidance Requirements For Simplified Onboard Control Of Moon-To-Earth Trajectories", NASA Langley Research Center, NASA-TN-D-6343, 1971.

3. The death of Gary Kildall also threads through the new texts I wrote for Arriving Simultaneously. In a personally startling coincidence, PC operating system pioneer, Gary Kildall, was mortally injured on July 8, 1994. The following day, July 9, 1994, while walking my bicycle in a crosswalk, a car ran directly into my leg. My leg was broken in about 14 places and I had a severed artery, but I was lucky that an ambulance came right away, and I lived, although I have been on crutches ever since. Gary Kildall did not live. He died a few days later on July 11.

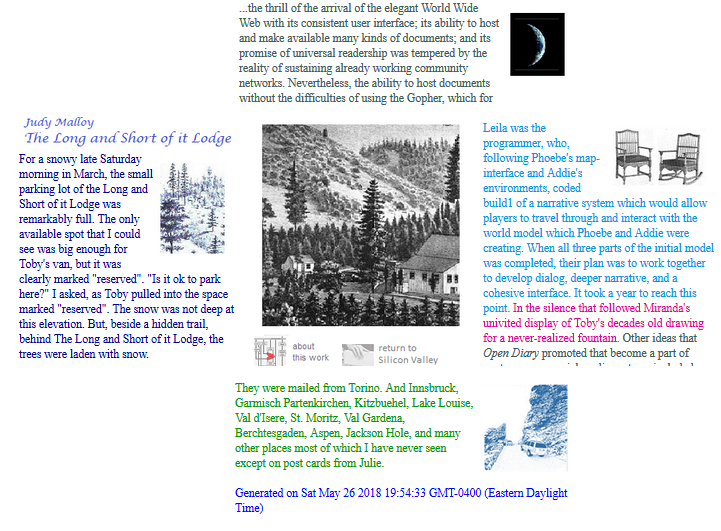

In a work that is composed with generative arrays, the reader may never see every word that was written, and yet, although every narrative detail that I insert into the code has the potential to alter the story, the reader does not see my stuggle to augment the database. Additionally, The new variables I wrote in the past few weeks will appear to the reader, interspersed with other variables, and in some cases the reader will never see them. Indeed, when generating output to illustrate this notebook entry, it was impossible to generate exactly what I wanted. August 28, 2018 It is a pleasure to report that Arriving Simultaneously -- which integrates randomly produced narrative in a polyphonic environment -- was shortlisted for the ELO Coover prize for best work of Electronic literature of the year! Arriving Simultaneously on Multiple Far-Flung Systems was partially born from a desire to make it clear that even though it is important to expose contemporary workplaces that are not hospitable to women, at the same time, we do not want to discourage young women from taking their place in computing environments of all kinds. As I noted in the "about file": "The gap between the acceptance of women programmers who worked during World War II and in the decades after World War II, and the much larger acceptance of men in the field in the 21st century is intrinsic to this narrative of one woman's journey from late 1960's information systems programmer in the aerospace industry in Colorado; to aerospace coder in Silicon Valley; to community network conferencing system programmer. In the process, the work explores hospitable environments for women in computing. " From the point of view of a woman, who began programming in the late 1960's, Arriving Simultaneously also documents the seemingly never-ending shifts -- not only in the technologies themselves, which in the 21st century continue to create an environment of life-long learning for those who work in industry or contemporary digital studies -- but also in technology funding. If considered as a rich environment of opportunities for life-long exploration, the former, has positive aspects, but the latter has the potential to drastically impact the job security of woman and minorities.

In a narrative data structure that allows the reader to move between traditional and aleatory narrative, The Yellow Bowl integrates a sequentially told narrative with a randomly (technically pseudo-randomly) accessed narrative. It was first presented at the historic 1992 MLA panel "Hypertext, Hypermedia: Defining a Fictional Form", where I said:

"In my narrabase, The Yellow Bowl, the contrast

The narrator is a single parent whose name is Grace.

The Yellow Bowl integrates two disparate structures

...pre-iconographically,

But, Following the MLA talk, YB was exhibited at the 1993 FISEA (the Fourth International Symposium on Electronic Art), in Minneapolis and also at Digital Identities, Sheppard Gallery, University of Nevada in 1995 (curated by Joseph DeLappe). Although YB was initially under contract to Eastgate, for a variety of reasons, Forward Anywhere (Malloy and Marshall, 1996) was published instead. Reconstructing The Yellow Bowl will not be an easy task. There are two initial issues. A. The work has 800 lexias. I have a printout of the entire text, and I have a printout of the original BASIC code. However, the disk reader I purchased last winter will not read the floppy version of YB that is in my personal collection. The idea of retyping 800 lexias is daunting, so I will first attempt to look for other copies and/or other methods of extracting the text. B. Earlier this year, I made the decision to first recreate the original BASIC version of YB and get it running on DOSBox. However, since Eastgate no longer owns this work, I am now considering reprogramming YB with JavaScript in an HTML5/CSS environment. It probably makes sense to recreate the original BASIC version first. But, the decision of how to begin has not yet been made. ----------------------------- 1. In the arts, coherent vision is also important and the question -- of whether or not (if they lived in overlapping time periods), a Giotto should repaint the Scrovegni Chapel to compete with a Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel -- might be considered an issue of Giotto's vision versus his desire to play on Michelangelo's stage. Contingently, on the Sistine Chapel walls, Michelangelo himself painted over not only some of his own earlier lunettes but also some of Perugino's frescos. (F. Brodie Lodge, "The Original Sistine Chapel Altar-Piece", Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 86: 4476,September 2, 1938. pp. 1026-1028) A virtual reconstruction is available at https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/early-sistine-art-brought-back-to-life-dwh5np8tl August 8, 2018

It was the intimacy of the early textual online environment that led me to use a first-person female narrator in Uncle Roger, a practice I have continued to use in subsequent works, including its name was Penelope, The Roar of Destiny, l0ve0ne, Difference that a Small Amount of Blue and Arriving Simultaneously. That a woman's use of a female first person narrator was also rare in print narrative did not occur to me -- until I looked at past instances of first person female narrators and saw how many were written by men. In Uncle Roger, initially I also thought of the narrator, Jenny, as an "agent", because at the time, this was an approach to the navigation of computer-mediated environments, an approach that has returned in the form of Siri, Alexa, and Cortana (Why not Bruce or Joe or Larry?). Additionally, the female narrator in Uncle Roger was a reaction to the "you" of adventure games -- where the narrative often implied that "you" was a man. I desired to radically change what was expected in computer-mediated narrative; I wanted a central woman's voice in the telling of a story that was situated in a male-centered environment. "The writer has us by the hand, forces us along her road, makes us see what she sees, never leaves us for a moment or allows us to forget her," Virginia Woolf writes about Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre. (The Common Reader, NY: Harcourt, Brace, 1948, p. 220) The first-person female narrator is not widely-discussed in electronic literature criticism. However, in Jaishree Odin's Hypertext and the Female Imaginary (University of Minnesota Press, 2010) it is a subtext (the use of a woman photographer's photographic memories in its name was Penelope, for instance). In her introduction, Odin notes: "I primarily focus on the mutation of narrative as seen in works created by women, for example, Trinh T. Minh-ha, Judy Malloy, Shelley Jackson, Stephanie Strickland, and M.D. Coverley. However, I also attempt to go beyond the mutation of narrative to see if such narratives can serve as a counterdiscourse to the homogenized and homogenizing dominant technocratic narrative through bringing out the significance of difference, whether cultural or gender, as it is enacted rather than as it is represented." (p.2) Contingently, given the importance of documenting the experiences of women coders in different eras, when I began writing Arriving Simultaneously, it did not occur to me that the voice of a female computer programmer -- whose adult life begins in the days when it was customary to hire women coders -- would be challenging for some readers.